HISTORY OF THE FAST AND VIGIL

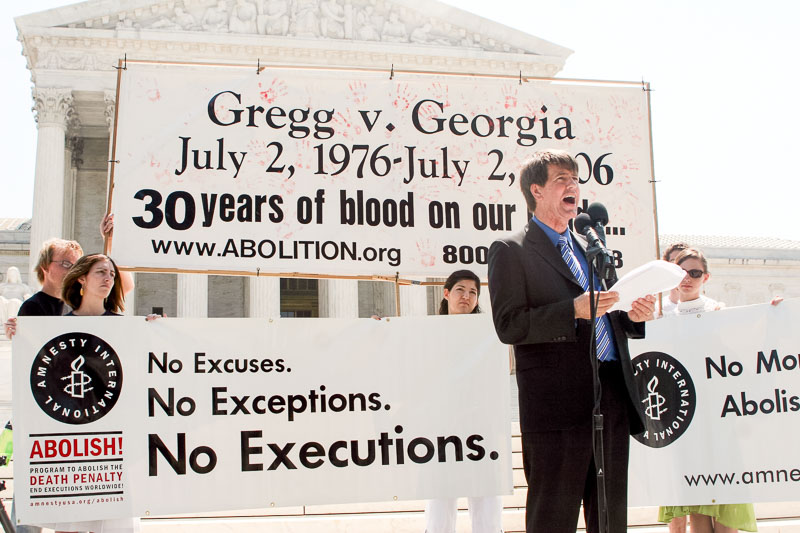

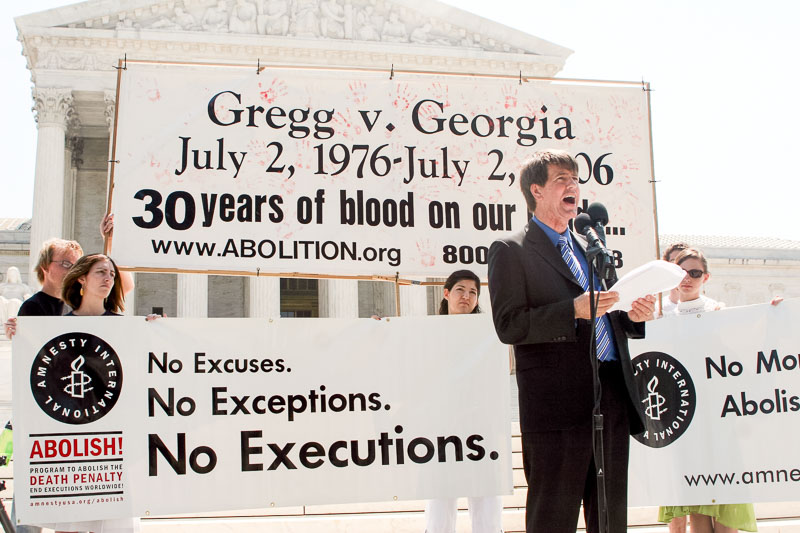

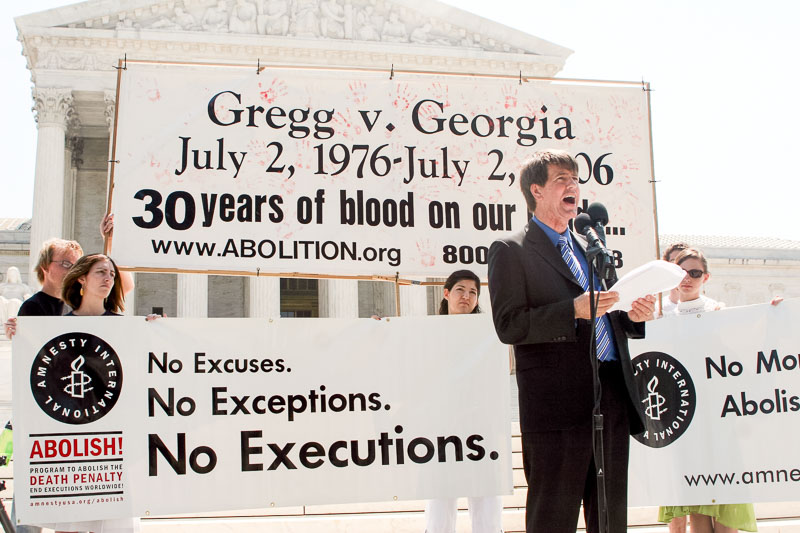

June 29 is the anniversary of the 1972 Furman v. Georgia decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court found the death penalty to be applied in an arbitrary and capricious manner. At that time, more then 600 condemned inmates had their death sentences reduced to terms of life imprisonment, and all states wanting to have a death penalty were forced to pass new death penalty laws. July 2 is the anniversary of the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia decision, which allowed executions to resume in the United States. The four days between these two historic anniversaries provide a natural opportunity for a demonstration of conscience on the issue of judicially-sanctioned state-sponsored killing. (Jump to below for more.)

The Abolitionist Action Committee (AAC) is an ad-hoc group of individuals committed to highly visible and effective public education for alternatives to the death penalty through nonviolent direct action. The informal committee of activists was founded in Dallas, Texas in 1994 by human rights historian Dr. Rick Halperin and two murder victim family members, Bill Pelke and Marietta Jaeger-Lane. Since 2017, Death Penalty Action has managed the events of the AAC as one of its programs.

The very first Fast and Vigil in 1994 was attended by a handful of abolitionists from across the United States. The annual event has since grown steadily, and by 1998 more than 150 people attended part or all of the event, including at least 30 individuals who fasted at the Court or in solidarity with those at the Court.

In 2001, more than 300 people attended the Steve Earle concert despite incredibly inhospitable weather and close to 40 people broke fast at the court at the end of the vigil.

The Fast & Vigil takes place on the sidewalk in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, considered by many to be the heart of the legalized killing machines in this country. In addition to the strong public witness, this is an excellent opportunity to meet other abolitionists and to "recharge your batteries" while engaging in public outreach and maintaining a physical presence at the Court. As always, fasting is purely optional.

Prisoners, activists from other countries, and abolitionists who are unable to come to Washington, D.C. have fasted or held events in solidarity with the action at the Court. This tradition continues to grow as well.

THE TWO HISTORICAL COURT RULINGS

June 29th is the anniversary of the Furman v. Georgia decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court found the death penalty to be arbitrary and capricious. More than 600 condemned inmates had their death sentences reduced to life. All states were required to re-write their death penalty laws. July 2nd is the anniversary of the Gregg v. Georgia decision, which allowed the resumption of executions in the U.S.

People have called this period of time a "moratorium" on executions, but that is not accurate. No body ever said "we're putting a halt to executions." In fact, no judicial executions had taken place in the United States since 1966. It could be said that there was a "de facto" moratorium, because it just happened to be that no executions were taking place. But the Furman decision changed all of that.

On June 29, 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty as it was then practiced was unconstitutional because it was random in its application. It was "arbitrary and capricious." The Court did not say that the death penalty was "cruel and unusual," and therefore a violation of the 8th amendment. So states were free to write new death penalty laws, and many states did so as quickly as possible. Florida was the first to write a new law, calling a special session of the legislature in November, 1972. Within a year Florida had its first death row prisoner. Other states wrote new laws, and by 1976, those new laws were being tested at the U.S. Supreme Court. On July 2, 1976, the Court upheld the new laws with its decision in Gregg v. Georgia.

On January 17, 1977, Gary Gilmore voluntarily waived his appeals and became the first person executed in the current death penalty era. He was killed by firing squad by the State of Utah in revenge for his murders of Ben Bushnell and Max Jensen. On May 25, 1979, John Spenkelink became the first unwilling prisoner to be executed in the current death penalty era, when he was burned to death in Florida's electric chair in revenge for his murder of Joseph Szymankiewicz.

Further Reading: